There is something very romantic about things emerging from under the waters: think the Lady of the Lake brandishing Excalibur, or a sunken town. Places such as the fabled Atlantis, Port Royal in Jamaica, Heracleon in Egypt, and storm-tossed Dunwich, generate stories of sunken church bells and ghostly apparitions. Some monuments escaped inundations: Abu Simnel was moved to avoid the rising waters of the Aswan dam while the architects of Rutland Water chose to protect Normanton church with a bund. As things stand, Venice will one day be faced with similar decisions if St Mark’s Square is not to slip below the Mediterranean waves.

The loss of Port Royal was instant and catastrophic; Dunwich took longer as the erosion of the coastline took centuries. For others it was the actions of man: the planned flooding of a river valley to create a reservoir.

When Stithians reservoir in Cornwall was created back in 1967, it engulfed several houses and small farmsteads. The slow rise of the water level must have been both tragic and romantic. Slowly, the water would have crept across fields, gardens and yards, ignoring man-made barriers. It would have trickled over familiar doorsteps, emerged from under floors, floated away abandoned toys, soaked carpets and walls and worked its way up the walls. There is something insidious about flooding, especially when there is no flow: a sense of the inevitable.

The rougher parts of Cornwall are rough for a reason: they are generally tracts of unproductive land with very thin soil or areas which do not justify the effort to clear away the many massive boulders which lie just below the surface. The Bronze Age fields and walls around Zennor are evidence of the enormous effort our ancestors put into clearing fields and turning rough ground into verdant pasture: the boundary walls constructed of immense rocks which previous generations believed must have been moved by giants.

One such rough area may have lain on the edge of the shallow valley beneath Stithians reservoir.

Water is both a destroyer and a cleanser. All the colours of the previous landscape and houses will eventually be bleached out by the lack of sunlight and vegetation will die back revealing the natural stone beneath. At Stithians, the water killed off the vegetation in an unproductive rock-strewn area at the margin of the new lake. It then scoured the area of any topsoil, revealing the archaeology that lay beneath including three groups of enigmatic cup-marked stones.

The story of the discovery of these stones goes back to the 1980s when water levels in the reservoir were sufficiently low for the stones to be exposed. After much research and field-walking, a series of flints and axes were discovered, sufficient to date the archaeology to the late Mesolithic (pastoralists) or early Neolithic (farmers). It remains an assumption that the stones date to this period.

The stones

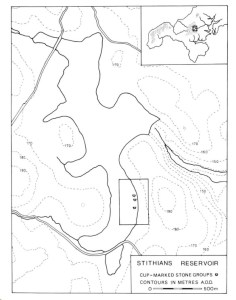

There are three groups, unromantically named A, B and C, each group being no more than 3m across. They lie on a rough contour line about 100m and 35m apart. There are twelve stones in all (5, 5 and 2), with group A being the largest and most obvious.

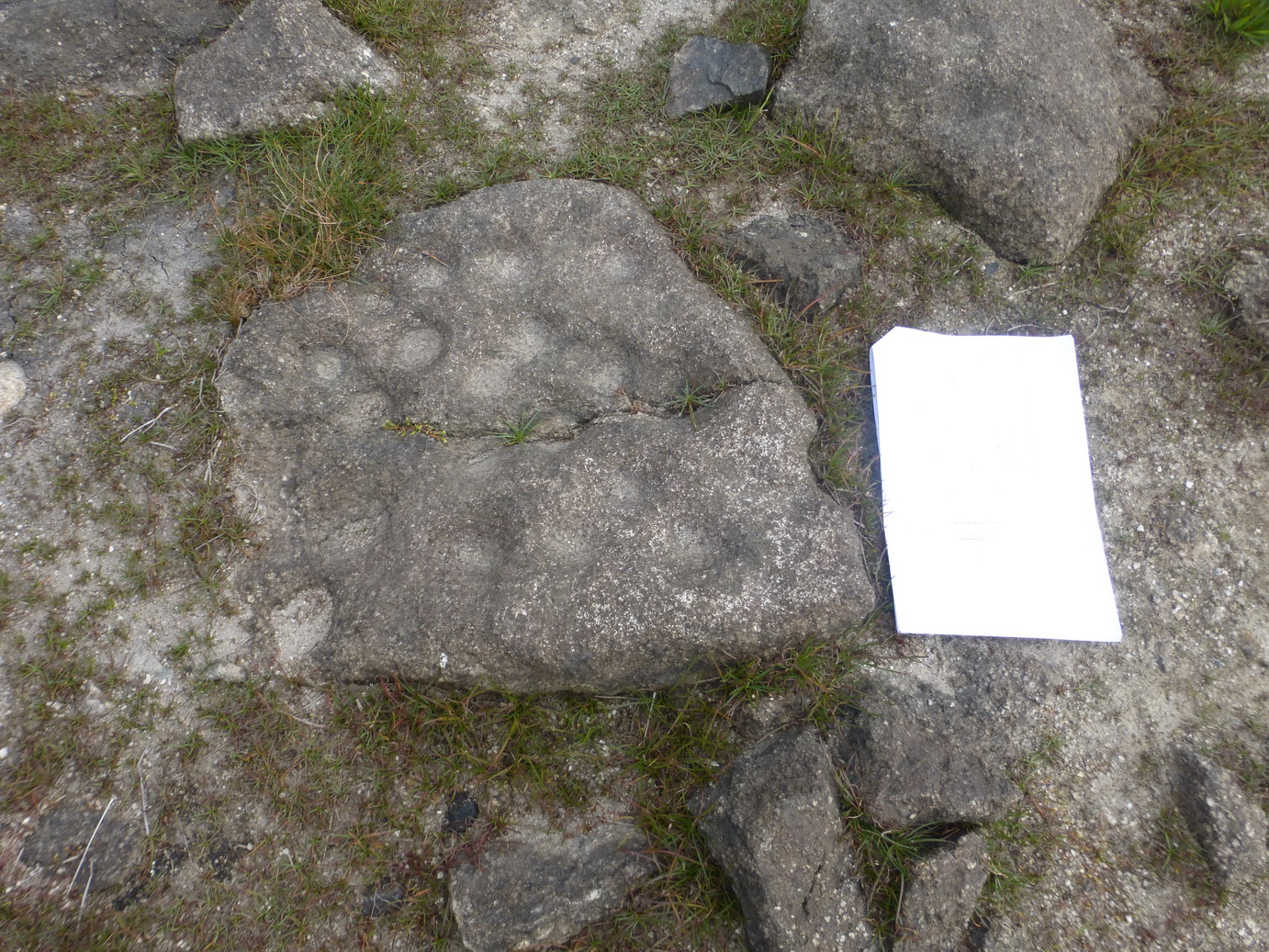

Once you get your eye in, the cup marks are very obvious: about 5cm across and 1-2cm deep. We discovered that it helps to have bright or low-angled sun as the two days on which we visited were very different. There is no obvious pattern to the markings. Some indentations are clustered to one side of their stone, others are scattered across the surface.

The original archaeological report explored, and rejected, alternative explanations that they might be natural features, socket stones, mortar stones, whim stones or industrial drill holes as they did not accord with other examples, concluding that they were contemporary with the flints and axes. This leaves us room to speculate on why our ancestors might have created them, surely one of the greatest enjoyments of ancient monuments: the opportunity to wonder why.

Artefacts like the Nebra Sky disk encourage one to look to the heavens for an explanation. Perhaps, like the the sky disk, they a record of the night sky, or some form of more permanent record: a calendar or something to do with the changing seasons? Or were they something as prosaic as the negative of a rubbing stone: where someone had sharpened the point of tool? Is there significance in the patterns, or lack of them? Were they votive in some way and, if so, what did they represent? We can only guess at the thinking of the past.

Certainly, cup-marked stones are generally associated with funerary monuments (eg Tregiffian near the Merry Maidens) and they are therefore seen as having ‘ritual significance’ (the usual archaeological cliche). The difficulty here is that there is no sign of any such monument.

Group A is much the most impressive, in two groups with stone 3 (possibly once joined to stones 1 and 2) being the most highly decorated. Is it a map of hunting grounds; of local villages; a memory of animal kills; a record of some astronomical event, or simply an early map of the HS2 network? Who knows?

Stone 5 is irresistibly similar to the ubiquitous mancala game of Africa (also known as Bao, or Omweso in Uganda), where beads are distributed into individual cups in a two-person game of strategy.

Group B is about 100m further north, just to the right of the path. The location map shows a prominent cairn which confused us. There are many piles of stones on the beach but Group B is not obviously related to any of them. Stone 6 is the most obvious here.

Group C is about 35m further north again. This is the smallest of the groups and only stone 12 is the slightest bit impressive. Again, it is slightly to the right (east) of the path.

Finding the stones

It is not easy to find the stones and we made several attempts before appealing to the ever-reliable Cornish Bird (to whom grateful credit) for help. Even then, we had to make two trips.

Much is made of the need to go at ‘low tide’ when the level of water in the reservoir is low. We visited when water levels were probably well below 80% and we estimated that two groups would be visible at anything up to 90% capacity as they are only just below the ‘normal water level mark’.

There is a rough sort of path which runs roughly along the high tide mark. Group A, the easiest to find, is just to the left of this. The other two groups are surprisingly high up the beach, to the right. Stithians is remote and What3Words was not in the best of moods but these three links may be helpful to get you close to the stones: Group A, Group B, Group C.

The easiest access is from the causeway road at the southern end of the reservoir but the more energetic may wish to walk right around the lake, past nature reserves, over the dam and (sadly) along a dull and faintly hazardous bit of road).

The first day we visited was a gem. The mist was burning off as the burning sun broke through, the air was still and the surface of the diminished lake was as calm as anything. Stone chats and linnets dogged our progress, hopping from rock to rock ahead of us. Two kingfishers flitted and sang around the a stream which was trying hard to fill the reservoir. Beneath our feet, a succulent green grass-like plant gave the illusion of a lush greensward. In a few short weeks it will once again be swallowed up by the encroaching waters, no doubt submerging the stones for another winter.

We repeat our gratitude to the Cornish Bird on this journey.